Farmer John Writes: Two Home Farms

Harvest Week 12, September 19th – 24th, 2022

King Charles

King Charles was discussed widely recently due to, amongst many other things, his upset about a leaky pen with which he attempted to sign official documents.

My wife Haidy said, “imagine everything he is going through now. It’s pretty normal to lose it over a small thing like a leaky pen when you are dealing with so much.”

From the article Charles to give up Home Farm ahead of future as king: “The Sun newspaper reported that quitting Home Farm near Tetbury in Gloucestershire would be a “wrench” for the prince, who has devoted decades to its development.”

I said to Haidy, “By his innermost nature, the King is a farmer, and a good one. A farmer has to make sure things work. A leaky pen is like a tractor that won’t start.”

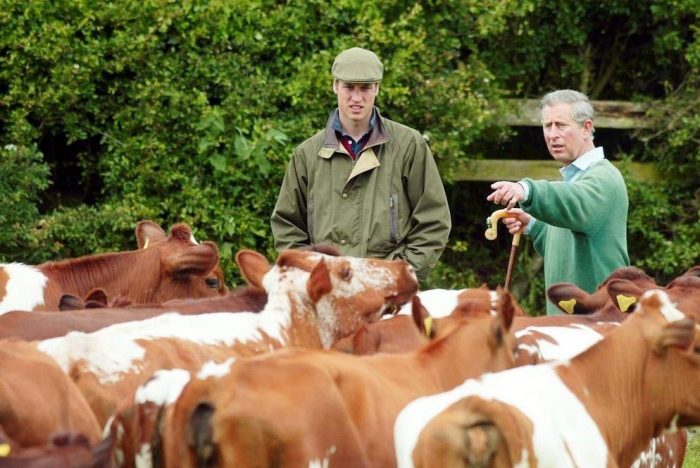

the Prince knows his cattle

My visual impression of King Charles is that he exudes farmerness, his stature aligned with the forces of the earth, his face creased by decades of caring for the planet. Learn more about the Prince (now King) and his farmerness in the 7-minute video The Farmer and his Prince.

I don’t know King Charles. It seems I was supposed to.

I toured many countries with the film about my life, The Real Dirt on Farmer John. There were mixed reactions to the film, which I can categorize somewhat by region.

The Scandinavians said, “we can only look at your film from a distance—objectively. We would never take chances with our lives like you did. For us, it is only a story, not a calling.”

The Germans and Dutch admonished me, “How could you lose your family’s land? Besides, don’t tell us how to farm or conduct our lives with propaganda about this American thing called Community Supported Agriculture. We know what to do. If Community Supported Agriculture was supposed to be here, it would already be here.”

The Italians and the Spanish said, sometimes weeping, “Your film means that we don’t have to grow up and become like our parents.”

There was, however, one unifying response from filmgoers throughout Europe:

“Prince Charles must see this film.”

“You know how to get it to him?”

“I have a friend whose cousin knows someone near where he lives.”

“Seems a little indirect,” I said.

“You and Prince Charles would hit it off. He would love you. You guys would have so much fun together. And he’s Biodynamic, too, just like your farm. Get him to see your film.”

“Off to see the Prince, Farmer John!”

I heard these sorts of suggestions dozens of times in pretty much all the countries where I screened the film. The destiny of the film tour seemed like a mission to track down the Prince. The huge effort of crisscrossing Europe with the movie for a couple of years started to make it seem like it was about meeting Prince Charles, and maybe to have fun with him.

I’m not prone to fantasy, but, after hearing speculative comments over and over about the Prince and me, I started to imagine, in a sort of separate reality, more deeply, or at least in more detail, what the Prince was like. In another dimension, I felt like I was getting to know him.

Due to so many suggestions to have Prince Charles see the film, with none of them backed up by realistic offers to actually get the film to the Prince, I finally took it upon myself to wrap up the dvd and send it to him at Highgrove House, realizing that it very likely would never get to him. Months later, I received a fax from his footman—yes, footman. This bearer of royal messages assured me that the Prince would be presented with the dvd.

That’s where it ended—with the assurance by fax that the Prince would receive the dvd. I never heard back from the Prince.

But weirdly, it didn’t exactly end there, because, by this time, due to the incessant encouragement throughout Europe, I had become an imaginary friend of the Prince. Well, I wasn’t really that engaged in being his friend. Mostly, I was imagining what sort of life he had, what he liked about it, what irked him about it, and how he actually walked when he traversed his estate, how his Wellingtons met the ground, how buoyant was his step, what did he behold in nature, how deeply had Rudolf Steiner’s work penetrated him, what were his primary yearnings for the world, for humanity. And admittedly, on occasion, I imagined the Prince and me doubled over in laughter. After all, he is a farmer, and farmers are often irresistibly funny.

I respect that King Charles got miffed by a leaky royal pen. He wants a world that works. He held in his hand an instrument which ideally could be guided, pointed, streamed into his cursive signature, his royal affirmation. However, this liquid column of ink sought to surge indiscriminately onto the page, to blob, mar, tarnish, to obstruct the intention. Prince Charles is a good farmer. His equipment, I am sure, is up to his standards. Bring those standards to the Royal Palace, I say.

Al Gore

I am going to make a leap across the ocean now, to the American version of a royal influencer, Al Gore.

Due to his enthusiasm for The Real Dirt on Farmer John, Al hosted some friends involved with the film production and me at his family farm near Carthage, Tennessee.

We walked his fields. He talked about his dad, Senator Albert Gore, about his dad’s love for rural Tennessee, for the small towns, the feed mills, the cattle farmers. Senator Gore even built an arena on the farm for showcasing and auctioning prize cattle in the area. Al said that his dad’s favorite thing in the year was to load up the family into the station wagon, clear out of Washington D.C., and make a beeline to the family farm, where he could enjoy the life he loved in the community that he loved.

Al said that one summer, when he was 16 and his dad couldn’t be on the farm, he was put in charge of the management of the farm. He did the plowing that summer.

“See that hill?” Al pointed to a nearby slope. “Too steep to plow with a tractor. I plowed it with a mule,” he beamed.

And the photos selected by Senator Gore for display in the farmhouse kitchen—all family photos, often of one of the Gore kids with a prize-winning steer at the county fair. (I believe you can see these photos in Al’s film An Inconvenient Truth.)

That weekend, while at the Gore dinner table, Tipper and Al asked me if I would help to rejuvenate their farm. It wasn’t a working farm at the time, though it hosted a most lovely aging sprawl of tobacco barns and other farm buildings. I gulped and said yes, but noted that I was very overcommitted at the time, with my own farm in operation and a very demanding film tour underway. Still, I said I would submit some ideas.

I am sharing these details of the tour of the Gore family farm to highlight that Al, the son, was once deeply embedded in the farming culture. However, I didn’t really sense that he yearned for it, that he ached to plow those hills again, to muscle up building a fence or hefting rocks. I sensed that he clearly appreciated his early life on that farm, but not that he was hoping to live into it again. Yes, at the time he was in consideration of developing and showcasing his farm as a model of sustainability, but I sensed little emotional or physical affinity from him for the actual life that a working farm has to offer. He seemed more attached to his idea of the farm than to the farm itself.

On the other hand, the tens of thousands of photos on the internet of Prince Charles walking and being on his land impart the feeling that he belongs there and that the land is there to love and support him. His Wellingtons are conduits between soil and soul. The Prince is of the landscape, of the earth. He is an essential and blessed element of the farm organism.

I feel otherwise about Al (who appears on his farm in just a few internet photos). I feel that for Al, his home farm is a reassuring story, a rich story that contributed to who he has become in life, and a laboratory that could help to save the planet. Prince Charles seems melded to the earth; Al Gore seems melded to concepts about the earth.

And that’s fine. Al doesn’t have to grab a shovel or a pickaxe and go to work on his land to be a good citizen of the earth.

But, I thought that Al had lost something important. So, when we spent time together months later in San Francisco, where he was going to introduce the film at the Castro Theater, I said, “Al, I think you should do some farming. I think it would be good for you, get on a tractor, go back and forth down the field, watch the soil pass under you, let the thoughts and feelings come. You don’t do that anymore.”

He turned towards me. “You offering me a job?”

“Yeah, I’ve been considering it. We could have you on my farm in privacy, no one would know, no press would be there…you would just be one of the crew, just for a couple of days.”

“How much you going to pay me?”

“Well, normal starting pay is $12 per hour. But since you’ve got some experience running equipment, and since you are in special situation, I’ll offer you $14 per hour.”

“Not enough,” Al said, turning away.

Al Gore’s Introduction to The Real Dirt on Farmer John

Here you can watch Al’s introduction to a screening of The Real Dirt on Farmer John at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco in 2006:

You can watch The Real Dirt on Farmer John here.

You wouldn’t surmise it from the introduction by Al, but shortly before his introduction of the film at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco, Al chastised me for being too personal with him. I suppose a case could be made for that, but, by this time, I thought Al and I had become fast friends, and I thought it was fine to discuss personal things with him while we were standing side by side at the urinals.

Not long after that, I read that Tipper and Al were separating. I sent them some preliminary ideas for re-enlivening their farm, but never heard from either of them again.

Warmly,

Farmer John