Farmer John Writes: One Cannot Understand Russia with the Mind

Introduction

Dear Shareholders and Other Friends of the Farm,

Twenty years ago, I wrote a story about the six weeks I spent in Russia. I am finally sharing it. I believe the story bears on the Russia of today.

For parents: this story contains some graphic imagery. I suggest you read it first, before deciding to share it with your kids.

For readers of Farm News: This story strays off the farm into Russia; it is not characteristic of my usual themes in Farm News. However, for the sake of getting to know your farmer better, and getting to know Russia better, I am sharing it with you today. The Russia you will get to know better is the Russia I visited and wrote about 20 years ago, but the story also bears on the Russia of today.

The story is simply reporting, an experience on the ground of the Russian people. Nothing is embellished or exaggerated. Until today, it was an unpublished and unshared story. (I have several more unpublished short stories and unpublished long short stories, all autobiographical.)

One Cannot Understand Russia with the Mind is a long short story. It is about a 60-minute read.

Ukraine

I was wondering recently about H-2A workers from Ukraine. The H-2A program is sponsored by the U.S. government for bringing in workers legally from other countries for a limited period of time. I had already selected my crew of H-2A workers from Mexico for the 2022 season on my farm, Angelic Organics. Still, I wondered about the Ukraine H-2A situation.

I called a service in Iowa, iWorkMarket, whose website says it specializes in procuring H-2A workers from Ukraine. The owner, Irina, answered the phone.

“Hello,” I said. “What can you tell me about your program for H-2A workers from Ukraine?”

“It’s a terrible situation. I had so many Ukrainians lined up to come work here. I had their visas in order. So many farms are counting on them. I now have to cancel their visas. They have to stay and fight. I am so crushed. I am lost.”

“So sorry to learn this, Irina. What can you say about Ukrainian workers?” I asked.

“They are the best. They don’t cause problems. They are neat. They take their shoes off to enter their homes. They are good cooks. They work hard.”

“What about drinking? Smoking?”

“Never a problem. Well, one smoked. I told him he would have to stop smoking to work in the States. He stopped.”

“Do you get to know these workers personally?”

“Many of them. Many of them work within a few hundred miles of me here in Muscatine. I go to the farms to visit them, or they come to visit me. They are simply the best.”

She added, “My husband wants to go and fight with them.”

“Are you Ukrainian?” I inquired.

“I am Russian.”

Russia

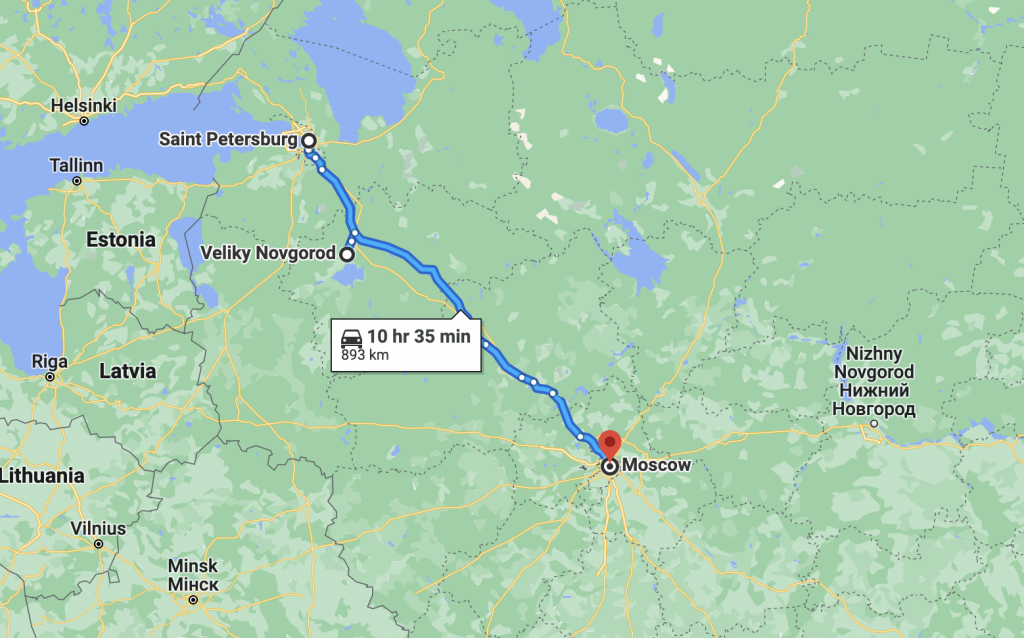

In the early 2000’s, I received the following email from my then partner, Lesley Freeman, who was living in Novgorod, Russia, also known as Veliky Novgorod:

“I was walking one day to the Mogilevskys’ place on my way home from yoga class. The Mogilevskys are a family of artists and musicians and they had adopted me as a daughter. I was walking along, thinking how glad I was to have this family, how they were making my stay in Russia feel absolutely like home, how anywhere, even cold, faraway Russia can seem like home if a person has the right people surrounding her. Then I heard a loud thump and turned to see a body flying through the air and land on the curb of the nearby busy street. I walked over, saw the woman up close. She was lying there in the wet, dirty road, body twisted this way and that, but still breathing. The brown car that had hit her had pulled over a ways up the street. I panicked.

“Then I heard a loud thump and turned to see a body flying through the air”

“A group of spectators had formed at the spot. I frantically insisted that a person with a cell phone call 911. The spectators watched me blankly and did nothing. I ran to the shop on the other side of the street, to the telephone shop. I thought, the shop will have a phone and call 911 for me. I was frantic. No one would call. My language skills were truncated under the stress, maybe no one understood my pleas. I went back to the site of the impact. The sixty-five-or-so year old woman’s purse was lying in the middle of the street, and no one was retrieving it. I retrieved it and as I did was shocked that no one was taking action at all, and that I actually had to myself. The old woman’s shirt was half off and no one was covering her. Someone finally did call 911.

“In about fifteen minutes the ambulance came. The emergency staff emerged from their antiquated vehicle–a dirtied white VW van-shaped vehicle without flashing lights or sirens that looked like it should also be admitted to the hospital immediately. They stood around like the rest of the spectators, doing nothing. They weren’t even covering this woman. I asked the woman in a white coat who was sitting in the vehicle if they could at least cover her right away. She said that this ambulance wasn’t outfitted for anything of this sort and that they had already called the real ambulance. The woman in white seemed tormented and embarrassed by the situation; it was obvious that she, too, was horrified that immediate help was unavailable.

“The real ambulance arrived in another ten minutes. It was a reassuring-looking vehicle, much like the kind in the U.S.–white exterior, blue flashing lights, blue cross on the sides. They opened the rear. A man checked the woman’s face. They got out a stretcher. They stood around. No one covered her. They put the empty stretcher back in the vehicle, then took it out again as they had decided to put her on it after all. It took three of them to get her on it. They pushed the stretcher into the ambulance and then stood around.

“I had begun to walk towards the Mogilevskys’ place at this point, sobbing, sympathetic, appalled. I looked back every so often; after thirty minutes the woman was finally inside the ambulance, but it had not yet whizzed her to the hospital. Emergency staff were standing around on the street discussing who knows what (perhaps what to do about the driver who hit her) and no police whatsoever had arrived at the scene.

“As I was resuming my walk toward the Mogilevsky family’s home, a place where it was quiet, homey, happy, loving, a man stopped me on the street to ask what had happened. I told him and he replied with a nonchalant “c’est la vie.” However, my mind at this time was filled with examinations about karma, fate, good, evil, love for one’s fellow human, the likelihood of Russia ever working properly as a country with a population to tend.

“I arrived at the Mogilevskys’ in a tearful condition, and though I experienced some sympathy from the mother, the father, a doctor, went on and on about whose fault was whose, about how pedestrians should look both ways when crossing the street, that when people aren’t on crosswalks when they get hit it’s their fault. Then he said that Russia simply has no money to support faster, better emergency service or effective traffic control. And he told me I need to understand better that Russia is not America–that, in Russia, life is difficult and unpredictable, that it can change any minute without warning. He said that, in this tough Russian world, people can really only strive to be good, kind individuals and go to work and not agonize over all the problems, lest they lose optimism for life completely.”

Lesley, a citizen of the U.S. who had once interned on my farm, by this time had already lived in Russia more than a year. Now she was studying Russian ecology and the Russian language through a fellowship. Lesley’s emails often made me think that Russia was an incomprehensible country.

Lesley Invited Me to Russia

On my flight to Russia, via Hamburg, Germany, I pondered what I knew, or thought I knew, about the country. I knew from the Weekly Reader that came to my grade school that the Russian satellite Sputnik had embarrassed the U.S. Since then, I had gotten sporadic, disjointed impressions of Russia from news stories and history books.

I was never much impacted by the Cold War hysteria. We never had to hunch under desks to practice for a nuclear attack. I never scanned the horizon to see if maybe the Russians had dropped a bomb on our cornfields. I remember that Nikita Khrushchev got mad and hit his shoe on the table on national television. My dad loved to talk about that. I can’t remember why he was banging his shoe; maybe he was raving about how great communism was, and how it would overtake capitalism someday.

Sometimes on television, Russian leaders embraced and kissed one another’s cheeks. I remember my dad saying that’s how it was done in some countries, that it was like shaking hands for us. I also remember from Life Magazine that Khrushchev, when he came to the U.S. in 1959, thought we moved cars around from one location to the next, so that he would see a lot of cars wherever he went. He was sure that a country couldn’t have that many cars wherever a person would go.

The thing about the Czars and emperors and Catherine the Great, Ivan the Terrible, the Bolsheviks, the White Brigade – these never came together for me in any kind of cohesive way – I simply could never get a picture of how things had unfolded in Russia. I remember reading that Russian history books were often getting revised to accommodate yet another official version of Russian history, so it seemed pointless to try to learn anything about Russia from Russia. I didn’t trust American accounts of Russia either; I figured the U.S would have its own vainglorious interpretation of their adversary or rival.

I did, however, in a sort of vague way, suspect that Russia was not given due consideration for the horrors it had endured during the Second World War, nor proper respect for its valiant role in resisting and overcoming the invading enemy. I don’t know why this feeling resided within me; it was just there.

Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment made me feel like I was getting at the true Russia, a Russia of deep love and terrible suffering. I read it out loud one winter as I traveled around Mexico. With almost every turn of the page, I sobbed. I sometimes wondered if Dostoevsky’s Russia had survived the twentieth century.

In late January of 2002, I flew to Russia via Hamburg, Germany, to visit Lesley. I was sure that I had a few stereotypes of Russia that had somehow gotten past my guard, but mostly I knew that I just didn’t know much at all about this country where I was going to spend the next few weeks. I knew that my main purpose there was being with Lesley and working on a book about my farm; that if Russia was going to get to me, it would have to sneak in around the edges of my intended life there.

I got off the plane with a swarm of German businessmen. They hustled in their black trench coats towards the customs station. They seemed like they were storming the airport–trot, trot, trot. They panted towards the Customs officials, literally running. German men running towards Russia – this is not new, I mused.

Embedded in the gray tile floor in front of the row of customs booths was a line of black tile. Fixed in this black line in the floor, in front of each booth, was the image of a man’s bony face, his eyes deep-set and shadowy, his finger to his lips. “Shhh….Quiet. Don’t talk. You are entering Russia, No talking”.

Lesley met me outside of Customs. She is little, with curly brown hair, a soft expressive mouth, and eyes that look askance in a way that make her seem perpetually mysterious, as though she is always feeling a secret. She plays guitar, mandolin and violin. She seems like she’s always got something exciting going on, something to wonder about.

God Wanted Us to Meet

Lesley and I headed into Moscow. One of the first things we did was go to Red Square. I thought there would be a tank sitting there, or a missile, but there wasn’t.

We used to celebrate May Day on my farm. We handed out May Day Baskets, and danced around a May Pole. Someone would usually mention the big military parade that was going on that day in Red Square. It didn’t seem like such a sweet use of May Day, but one year, we had vodka maple syrup snow cones at our May Day party to honor the Russian Military May Day.

The huge expanse of Red Square was now a mecca for hawkers. Enterprising Moscovites were selling furry Russian hats (ushankas) to tourists caught unprotected from the frigid Russian wind. Others hawked mittens.

We walked to the perimeter of the Square and discovered great arenas of commerce. Tom Tailor, Dior, Versace, Swatch, Gentlemen, Marina Rinaldi, Clinique, Pioneer London, Escada, Benetton, Cachere, Articale, L’oreal–Red Square was surrounded by a massive shopping emporium. Lesley and I wandered the grand and sometimes garish edifices hosting these fashion empires.

A deaf/mute man approached us, and gesticulated. We could not understand what he wanted. I offered him rubles. He refused. He showed us bruises on his stomach and legs. It seems he had been beaten, there, in the emporium, in a staircase.

We later found ourselves in the upscale Great Canadian Bagel. Our waitress, Julia, was in her mid-twenties, bright, open faced, long brown hair, big brown eyes. There weren’t many customers, so Lesley, she and I got to talking, and soon Julia started telling us about her life. She was Muslim, had fallen deeply in love, married, had a child, then a second. Her husband had gotten in trouble with the law, and two years ago he had been sentenced to four years in a Siberian prison.

(Note about Lesley and her Russian: Russians everywhere were most pleased by Lesley’s mastery of the Russian language. Many Russians said that Lesley spoke like a Russian. Lesley was the always-willing translator. My interactions with Russians recorded in this account were via Lesley’s translation, except for the occasional times when the exchanges took place in English.)

“My husband is a good man,” Julia proclaimed. “He just got in with the wrong crowd. But it has been so hard; my mother has taken my children and me in to her home. If my mother had not helped me, I don’t think I would be alive today. For a while, I didn’t know how I would feed my kids. Now that I am working at this nice restaurant, I can feed them.”

“Do your kids know where their dad is?” I asked.

“I tell them he is at a hospital. When we visited him in prison nearby, before he was sent to Siberia, my son saw him through all the thick glass windows. I told him it was so no one would catch his disease.”

“Is there any way you can get your husband out early?”

“The government said he could get out early if I came up with $1,500. An attorney had all the papers drawn up. So, I took my jewelry that I had gotten for a wedding gift, worth $3,000, and sold it for $1,500. On my way back from where I sold it, I was robbed.

“I thought there might be another way to get him out, as that was the only $1,500 I had access to. I went to another attorney. This attorney wanted money up front. I sold my fur coat, and got $100 for him. The attorney simply disappeared. I never saw him again.

“Then I finally somehow got all this paperwork done, petitioning for an early release, and it was in my mom’s car, and my mom’s car was stolen, along with all the paperwork.”

Julia went to check on another order. I sobbed, trying to conceal my tears from her. Russia, I thought, this is Dostoevsky’s Russia, a country of deep love and terrible suffering.

She returned to our table, “I have my faith in God. And I love my husband very much. He is a beautiful man. I will always love him.”

She added, “God brought you into this restaurant today. God wanted us to meet.”

As we were leaving, Julia said to us, “and you two. Are you going to get married?”

Lesley and I looked at each other and smiled.

“Please invite me to your wedding,” Julia requested.

Later, Lesley would share the love story of Julia with her favorite Russian family, the Mogilevskys.

“Lies,” the family said. “All lies, just to get your money. It is the Russian way.”

The next night, Lesley and I took the train to Veliky Novgorod, a seven-hour trip north west from Moscow. We sat next to a young, cheerful, attractive, university-educated Russian woman. After a bit of engaging conversation, I asked, “What do you look for in a man?”

“First of all, he brings home money. A man’s first responsibility is to bring home the money. If he can’t do that, he really has no worth.”

Lesley noted later that many Russian women had echoed this sentiment to her.

The Once Illustrious Novgorod

We arrived early in the morning, and took a cab through the Russian cold towards Lesley’s apartment.

We passed through a commercial section of the town. Trees were scattered about. Georgian style buildings flanked the street, hinting in the early dawn at their soothing pastels and staunch, reassuring forms. Inscrutable words in Cyrillic script advertised shops and services.

We were soon out of the commercial area. Gloomy high-rises in every direction loomed towards a gray sky.

From a Novgorod travel brochure: “Novgorod is a city of 250,000 people. It sits on the Volkhov River, just below its outflow from Lake Ilmen. It is the earliest international trading center of Eastern Europe, starting in the eighth century. It is the earliest center of education of Russia, beginning with a school for 300 started in the eleventh century. Novgorod is widely regarded as the birthplace of Russian democratic, republic traditions. Medieval Novgorod was one of the greatest art centers of Europe. It was a major center of book production. It boasts the oldest church in Russia, Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, built in 989. It was once the political center, the capital of old Russia, Russe. Due to its splendid architectural beauty, Novgorod was for centuries regarded widely as the Florence of Russia.”

In the late fifteenth century, Ivan the Terrible plundered Novgorod the Great, and took away its status as political center/capital, and even stripped The Great from its title, reduced it to simply Novgorod.

Novgorod experienced heavy blows to its early glory. However, it remained a splendid city, a living testimony to a thousand years of Russian culture.

Then came its biggest blow. Early in the Second World War, the Germans leveled Novgorod.

Lesley and I were riding through this once illustrious thousand-year-old Russian City, but it had been completely rebuilt in the last fifty years. Barely a trace of its former majesty remained. After a few minutes, we arrived at Lesley’s apartment on the fourth floor of a gray high-rise.

“Welcome to my world,” said Lesley, gesturing to her home. I quickly explored the two-room apartment, eyed its drab wallpaper, its ragtag collection of furnishings. I noticed a huge map of Russia spread out on the wall above Lesley’s kitchen table.

“It has a certain Lesley hominess to it,” I offered.

Lesley smiled.

I looked out her kitchen window at the dozen or so residential towers that formed a perimeter of the view. Their boxy balconies seemed to be in a continual process of collapse. These protuberances of concrete were molesting the very sky above them. The gray of their shabby, crumbling walls was sucking the color right out of my face.

“Those buildings are ugly, Lesley, so depressing,” I commented.

“Agreed, but when you open a door to go into a home from the stairwell, it’s cute and pretty and clean and homey.”

My gaze turned downward. Below me was a cluster of charming old cottages, incongruously flanked by the concrete towers. Some of these cottages were built of logs, others of wide planks. They were sturdy, one-and-a-half floor structures, modest, but with occasional architectural flourishes. Some had intricate designs carved into their eaves, swirly wooden emblems in various colors attached to their walls, curly-cued trim around their arched window.

A few of the houses were painted in vivid colors; mustards, greens, blues. The windows and eaves were festively trimmed in complementary colors. The cottages were not fanciful, but hearty and cheerful—outpourings of the Russian folk spirit. Some of the homes had a little hut in the corner of the yard that served as the banya (Russian style sauna.)

All of the homes had space for vegetable and flower gardens, perhaps a fruit tree. The home just below us had snow-covered raised beds in its front and side yards. There was an aura of neglect that pervaded some of the homes, as though the encroaching parade of high-rises was soon to level the remaining community of cottages, a different sort of conquest than that wrought by the war, but with a similar outcome.

“Lesley, these houses are so great,” I said. “Here we see the old Russian spirit at work–the charming architecture, not at all ostentatious; the banya, the space for flowers and vegetables. These people are living on the land in the city. It’s urban agriculture right before our eyes. I wonder if most of them like it in those homes, or if they are just waiting to get into those high-rises. We’ve got to meet someone who lives in one of these homes.”

“We can probably do that”, Lesley said. “It is not an easy life, in those homes. They have no running water, no central heat, and no indoor toilets. They have to walk to a public well and pump their water by hand into buckets and carry them home.”

Lesley added, “And then there are the private houses of the new rich—they are referred to as the New Russians. You see them about town, huge imposing homes. With Perestroika, most people got poor, but some got very, very wealthy.”

“Speaking of money, I think I left my purse on the train,” Lesley said. “It had maybe eighty dollars in it, and some important papers.”

We returned to the station in pursuit of her money and papers. The train was no longer there.

I wrote for the next few days. Occasionally, Lesley and I milled about Novgorod. Except for the fur coats worn by some of the women, almost everyone dressed in black. The people of Novgorod looked somber.

“This grimness that I feel. Is it the economy? Everyone seems so freaked out, like they expect something awful to happen any second,” I observed.

“It’s the Russian way. Many people have two jobs. People wonder how they will put food on the table. And life for Russians is so unpredictable; there’s no telling what could happen tomorrow, no way to count on stability, or that anything will go as planned or expected.”

Lesley and I sat on a bus, aglow in animated conversation. The other passengers stared at us sullenly. “Look at how people stare at us, Lesley. And if I stare back, they don’t look away.”

“Russians stare. They stare a lot, right into your face. And they will never look away if you stare back.”

“No one on this bus is talking; not one person is smiling, except for you and me,” I observed. “They all dress up as much as they can afford to. Everyone’s shoes are polished. Women cake on the makeup. They all seem to want to look like they aren’t poor, and look as much like one another as they can.

“And then there is you, Lesley. Rumpled. Patched blue jeans. Candy cane scarf. You are one of the most affluent people on the street, and you look like their idea of a bum.”

“Yes, I guess it is a mark of affluence to dress like I do–American style affluence. But I just look different anyway. Curly hair. Different face. I would look different no matter how I dressed. And then I am with you. You don’t look Russian.”

“So many of them have bow lips,” I stated. “Have you noticed their mouths? Shaped like cute little bows. Even on a broad face, there will be this narrow little mouth, creased at the corners, all puffy and adorable.”

We got off the bus, walked down the icy sidewalk.

“Lesley, that babushka (grandma) back there, sitting on the sidewalk. She has four carrots for sale, and maybe six turnips. She is just sitting there, in the cold night. Will anyone buy her carrots on a Sunday night?”

After a few days in Novgorod, Lesley again went to the train station. She located the train we had ridden from Moscow and found the woman who had been in charge of our train car. A passenger had found Lesley’s papers and money, and had given them to this attendant, who had safeguarded them in the hopes that their owner might return for them.

The attendant gave Lesley the purse with all the papers and money inside. Lesley gave her a twenty-dollar reward. The attendant invited Lesley to her home in Moscow, a very Russian gesture.

A Russian friend later told Lesley that this woman probably made fifteen dollars per week. This return of the purse caused Lesley and me to talk about honesty, about integrity, about the old Russian ways.

That night, an American friend of Lesley’s was assaulted outside a Novgorod grocery store, was badly beaten up. The four men made off with about a dollar’s worth of rubles.

I met Lesley’s American friend, Bradn. Bradn was soft-spoken, considerate, and generous in talking and listening. An apprentice minister, he had a small Lutheran congregation in Novgorod, supported by a German Church group. In 1933, the communists closed The Lutheran Church in Novgorod. A couple of people in Bradn’s congregation remembered attending it back then as little children. It had reopened in the 1990’s.

“Bradn,” I said to the minister, “how was it for the people in your German congregation during the war?”

“Oh, they didn’t fight. They are all Germans. They were shipped off to camps.”

“What was it like for them when they came back?”

“They didn’t get to come back for a long time. Some of them came back five or ten years after the war was over; some didn’t get to come back for thirty years. That’s just the way it worked here. The government decided when someone returned, and sometimes it was just the bureaucratic process itself that took years, or decades. Sometimes it was more a form of punishment, for one reason or another.”

One afternoon, Lesley and I met a babushka coming out of her Russian cottage, a few blocks from Lesley’s apartment building.

“When were these built?” Lesley asked the old woman in her friendly, curious way, as she gestured towards her house.

“In the 50’s,” she said.

I thought, how could they make these homes so cute and detailed right after the war, right after their whole world had been laid to waste, when resources were so scarce, and now, sixty years later, they can only build impossibly ugly things that do not go an iota beyond the most basic utilitarianism? How could the Russian people, with roots so clearly in the country, in the soil, be so abruptly deposited in austere high-rise apartment buildings, no vegetables in their yard, no family banya out the back door, no chickens nesting in the lean-to? How was this leap so suddenly made?

The babushka took a liking to Lesley and me, and invited us for lunch. She had bright eyes, unusually smooth skin for her seventy-eight hard-working years, and a very alert manner. She sat us down in her cozy dining room to a meal of chicken soup, fish, and bread, with a little vodka.

“Lesley tells me that you had quite a time of it during the war,” I said, after a few minutes of their conversation in Russian, which Lesley had just summarized for me.

She replied, “I was in Leningrad during the war.”

(Note: Saint Petersburg was called Leningrad for a while, so I will use the names a bit interchangeably in this account.)

“I was seventeen years old. The Germans blockaded us for 900 days. My aunt died of starvation in the second month, just fell over. There was no food. There was a bread ration, 250 grams per day and 100 of that was clay. People chased after rats to eat them. I buried so many people.”

“How do you feel about Germans today?” I asked.

“How should I feel? They destroyed our cities. They tortured our men. They killed our people. What should I feel?”

She continued, “I have lived in this house for fifty years. I work hard every day. I chop wood. I take care of my fourteen chickens. I take care of my house. My husband died twenty-two years ago.

“I didn’t think life would be like this in my later years. The war seemed like it was the worst that life could be, and it seemed like when it was finally over, life would be so much better.

“But now people get killed right outside my door. There never used to be killings in this town, never. Three murders just this year. And people get robbed around here. People are so hungry today, they steal cats and eat them. I had two cats. I have one now. Some people ate the other one. What kind of a world is that?

She continued. “I went over to the phone company two years ago. I said ‘I want a phone. You put in a phone for me. I’ve been waiting fifty years for a phone. I’ve been promised a phone for fifty years. Where is my phone?’ And the guy said, ‘lady, don’t think you are getting a phone for free. No one gets anything for free.’ I said, ‘I was in the front! I was in the blockade in Leningrad! I defended my country! Your country! I want a phone. Is that too much to ask for defending this country?’ And they finally came over and put in my phone, and while they were at it, they put in phones for all the war widows in all these homes. Took ‘em a day. One day. We all waited fifty years, and when someone finally decided to do it, we all had phones in a day. That’s all it takes is someone deciding.”

“I was in the front! I was in the blockade in Leningrad! I defended my country! Your country! I want a phone. Is that too much to ask for defending this country?”

The babushka went into another room, came back with a vest loaded with military medals. I don’t know if they were all hers, or hers and her late husband’s.

“Every year, the ones around Novgorod who were in the blockade meet. I won’t go any more. The group is shrinking so fast. They are all getting so old. We are all getting so old.”

“You like living here?” I asked.

“Yes, it is my home. I have my garden. I have my chickens. But the government plans to knock it down, to put me in one of those cages they build. Just a cage, that’ s all they are.”

“I notice they have pretty much leveled the homes just a block down the street from you,” I said.

“Can’t you tell them you don’t want to go?” asked Lesley.

“The government doesn’t care what I want. They don’t care about me. They don’t care about the Russian people. They just do what they want. They took almost all my savings that I had in the bank. Took everyone’s pretty much. Just a few years back. My daughter gets twenty dollars per month for her pension. She can’t live on that. I have to help her out with my pension.”

“Do you have anything you are happy about?” I asked.

“I didn’t think it would be like this.”

“Are you happy when your chicken lays an egg? Are you happy when the sun shines through your window?” I asked.

The babushka tried not to smile, but finally, she looked radiant, and years younger. She was grinning ear to ear.

A Wheel Chair and a Palace in St. Petersburg

Lesley and I made the four-hour train ride north to St. Petersburg for a long weekend.

St. Petersburg seemed an odd city for Russia. It has a very western European mood about it. It has huge parks, immense ornate churches, wide boulevards, hundreds of museums, a wide range of ethnic restaurants, and palatial edifices, the greatest being the winter palace of the Russian Emperors. Some historians allege that the city was built as a message to Western Europe that Russia wasn’t a cultural and architectural backwater.

In St. Petersburg, many clubs were being revived that had been closed during the Communist period. The English language papers were full of promotions of these clubs: a dance club that had been closed for seventeen years, a performance space that had been closed for twenty-three years. There was even a music club that had been closed for eighty years that was reopening. I wondered who kept these memories alive so long; who was walking around thinking gee, I sure did have a good time at that club eighty years ago. I think it’s time to give it another go.

Nevsky Prospect, the main thoroughfare of the city, was lined with upscale consumer stores, fancy coffee shops, a small palace here and there, an occasional magnificent church, and many international chain hotels. (Out of curiosity, Lesley and I checked the rates at a Radisson – $450 U.S. a night for their cheapest room.)

On the Nevsky Prospect sidewalk in front of these opulent edifices, a frantic woman approached Lesley and me, “Please buy a map. My baby sister is so hungry. Please, just one map.” Another woman offered her mittens for sale. A rosy faced, young, handsome man, a veteran without legs, sat in a wheel chair wearing a military jacket, his hat extended for donations.

One very cold night, Lesley and I went to a Chinese restaurant. We chose not to sit in the main dining room, as there was loud music playing there. (Almost all upscale restaurants in Russia had very loud pop music blasting away. The music drowned out all conversation; one could eat, drink, gawk, and listen to music, but conversing was not possible.) We found a relatively quiet dining area near the entrance.

Shortly after sitting down, a blast of cold air suddenly swirled around us. Upon investigation, I discovered that the entrance door had blown open. (It was not visible from where we sat.) I asked the waitress to close it. She did. In a minute, it blew open again. I got up and closed it, sat down. Again, it blew open. Frigid wind blew through the restaurant. I closed the door again. Again, it blew open. I looked for something to prop against it. Of course, this would prevent customers from entering, or they would push over my barrier upon entering and create quite a disturbance. I wondered for how many years this door had been blowing open.

When we were done with our meal, the waitress cleared our table. She piled plates on her arm, higher and higher. I thought, she doesn’t know how to pile plates, bowls, and cups on her arm. She is just imitating someone piling plates on her arm, maybe a waitress she had seen and admired in a movie. After the stack of dishes got very high, it started to wobble. It suddenly shifted. She reached for it with her other arm. Good, I thought, she is going to take off a few plates, and make two trips. But no, she adjusted her stack of dishes, and then added more to the stack. It became preposterously high, comically high. I readied myself to leap for the falling dishes. She walked briskly away. The dishes spilled. I leapt. I missed all of them, as they clattered to the floor.

A little more about Russian restaurant service: it is a term that easily merits the status of oxymoron. For example, once, we asked for our blintzes with our appetizers. The waitress brought them as dessert. We said, “We asked for the blintzes with our appetizers. We thought you forgot them.”

The waitress said, “I know, but I thought they would be better as dessert.”

Another time we placed our order and said, “We are in a hurry. Can you please serve us quickly?”

There was one other customer in the restaurant. The waiter disappeared into the kitchen, returned several minutes later, and asked, “What things would you like in a hurry?”

We answered, “Please bring us things as they become ready in the kitchen.”

The waiter disappeared into the kitchen, came back several minutes later, and said, “The kitchen says that we can bring things as they become ready. Do you want me to put in your order?”

We replied, “Please, immediately. Can we have coffee?”

There were normal sized coffee mugs in tall stacks on a neighboring table. The waiter brought us coffee in demitasse cups.

We asked, “Why are these cups so small? These are not coffee cups.”

He said, “If you want a normal size cup, you have to ask for it; otherwise, you get this size.”

Because service was often so slow, we usually tried to get our check while we were eating our entrée. Often, when we were trying to get our bill, there would be several waitresses in a corner chatting and smoking. We would wave our arms, wince, gesticulate, and cough loudly to get their attention, just so that we could pay our bill.

The waitress would finally just come and slap our check down on the table.

This was not just a slight of Americans; many Russians corroborated this impression of Russian restaurant service. Restaurants really didn’t seem like they belonged in Russia; they seemed like impositions on the culture–odd, considering how fantastic Russian home cooking was and how gracious and hospitable Russians were in their homes.

While in St. Petersburg, we took a ride to Pushkin, a small town nearby where the Russian emperors had their summer palace, (built in 1710-1714 by Emperor Peter the Great, as a present, a rural retreat, for his wife, Catherine the Great.)

The drive from St. Petersburg to Pushkin is through a ghetto of crumbling warehouses, monstrous gray factories (many abandoned), piles of junk and industrial refuse, drab apartment buildings, on a completely broken highway with occasional stretches of deep pooling water in it, as there was no system for draining away the melted snow.

I wondered: how could so many public works by such a powerful country as Russia be so collapsed, so slovenly, so lacking in foresight? This is a country that prides itself on its engineering feats, but it does not require an engineer to know that water needs to drain off of highways. It doesn’t take a genius weather consultant to know that water freezes in Russia, and that frozen water will bust the roads, so it is better to not have the water there for it to freeze.

I wondered what the view was for the emperors when they journeyed from winter palace to summer palace, if they would have banned urban squalor from their view.

The summer palace was immense and gilded. Something seemed not right about it, though. Didn’t this structure go back several hundred years? I wondered. No, it turns out that it was almost completely demolished by the Germans as they approached Leningrad. And the German troops cut the ancient trees on the grounds to keep from freezing as they shelled Leningrad.

The summer palace was a reproduction, basically, an echo, of the Russian Empire’s opulent past.

Lesley and I put the required green plastic booties on, and wandered through the palace’s cavernous chambers. It felt wrong to me. I didn’t want to be there, protecting its reproduced floors with my green booties. I leaned against a wall. The guard reprimanded me for touching the wall. But this echo of your past needs life, I thought. It needs a smudge of life here and there.

Some rooms had photos of what that chamber had looked like after the Germans had destroyed it. A rubble wall here. A piece of floor there. We came upon the amber room, being slowly restored by grants from a gas company in Germany. There were little promotional brochures about the wonderful German gas company which does business in Russia. I thought of the Germans getting off the plane that had brought me to Russia, how they had run towards the immigration area, now soldiers of commerce.

I pondered: why did the Russians ever rebuild this palace anyway? Didn’t it represent everything that communism was opposed to: opulence, oppression of the poor, elitism? Why rebuild a memorial to a time that communists found revolting? Why didn’t they put that money into road drainage?

And Catherine the Great–didn’t she summer in this palace and collect massive works of art from Western Europe? Has she reincarnated since those days? Could she be a sullen guard in one of the palace’s gilded rooms? Perhaps she is the guard who admonished me not to touch. She sits there, in the reconstructed palace, day after day, protecting the walls, not recognizing her ancient home, not remembering her dinner extravaganzas, her art collections, her lovers. But every few months, while sipping tea on her break, something about the palace seems strangely familiar to her.

We headed back into St. Petersburg. It was awash in lights and shops and bars, much of it also an echo, a reproduction of its former overwhelming, incongruous western European grandeur. Could we really have an idea, even slightly accurate, of life within this city, during the blockade–no running water, no electricity, often no food, for two and one-half years, the coldest two winters of the twentieth century. Eating rats. Eating corpses. Shells raining down on this transplanted architectural extravaganza, laying it further to waste each day. Is this part of the somber mood that so many Russians carry within them? The war was finally won, but what was lost? Are Russians still in grief about the immensity of this trauma to their world? Does the next generation, and the next, take this grieving on, perhaps unconsciously?

In Russia, when you want a ride, you just put your arm out. Every fourth or fifth car will stop. You bargain a price, and away you go. These cars are not certified taxis. They are driven by moonlighting Russians. It is a standard way to travel about a Russian city (and I consider it a general barometer of how safe Russian strangers are to be with; if the drivers weren’t safe, it wouldn’t be a universally-used system.)

In St. Petersburg, one of these cars gave us a short ride. The driver’s name was Igor. He was a handsome, broad-faced man in a dressy leather jacket. When we mentioned we might want a ride to Novgorod, he told us that he wanted to take us there. We agreed on a price, and the next day we headed off on the four-hour journey to Novgorod, Lesley and I both in the back seat.

As he navigated his way through the squalid, chaotic outskirts of St. Petersburg, he began to tell us about his life. He had training as an engineer, but ten years ago he had lost his job, as engineering opportunities had almost completely vanished in Russia. He had savings then, and since then he had amassed more money working for a tractor manufacturer, rebuilding tractor engines. He had sent his wife to medical school, and she had become a doctor.

We sloshed through a kilometer or so of water standing in the highway. Hulks of tractors and trucks were scattered in the mud throughout the lots that flanked us. Men in rubber boots and coveralls waded about, carrying pipe, hoisting hunks of steel with the occasional working forklift. Collapsed buildings languished in the background.

Igor continued. He had $100,000 in the bank when he went to bed one night a few years ago, and the next morning he woke up, and he had $25,000. It must have been the same event that had happened to the babushka we had met in Novgorod, the one who had been in the blockade. Somehow, the government had suddenly impounded everyone’s savings in Russia, one of those devaluation strategies that bails the government out, and ruins millions of its citizens. For the last two years, Igor had made no money. He had been living off his savings. Five days earlier he had run out of savings.

“But your wife is a doctor,” I said. “Can’t she keep things going?”

“She makes fifty dollars per month as a doctor. Doctors make nothing.”

“How does she feel that your money is gone and you are driving a cab now?”

“She doesn’t know my money is gone. And I’ve been telling her I am out looking for a hard-to-find car part these last few days.”

He spoke with a peculiar energy, singing his words out robustly, snappily, enthusiastically. Rather, his speech seemed like a valiant attempt at enthusiasm.

“How come your country has so much money?” Igor asked. “It’s just got so much. What is their secret? You don’t have to tell me. I know the secret. It’s the Illuminati. They are here in Russia, too. But in Russia, they take the money out of the country, and give it to the Americans. I know all about the Illuminati.”

Igor told us he had wanted to take us to Novgorod, because a true pagan culture had flourished in that area 1,000 years earlier. Not long ago, he had become a member of this recently revived religion. This religion gave him hope for his life, his family, for Russia. A few weeks earlier, in front of his wife, he had taken his cross off his neck. He had told her he was done with Christianity. He was taking up the old way, the ancient way, from before when the Christians came to Russia and corrupted Russian folk life, the pure spiritual life.

“It’s the Illuminati. They are here in Russia, too. But in Russia, they take the money out of the country, and give it to the Americans. I know all about the Illuminati.”

The old way had a code, a simple code. There were four rules for the men: 1) be in relation to your surroundings; 2) protect your family; 3) pray to the old nature gods; and 4) tell the truth.

There was one rule for the women: obey your man.

“Is your wife interested in this pagan religion?” I asked.

“I’ve taken her to one meeting. She doesn’t seem to want to go back.”

“Are there any women who belong?” asked Lesley.

“A few,” Igor answered.

I thought of the conversation Lesley and I had recently had with the young woman on the train to Novgorod weeks earlier, when she had stated that the man has no worth unless he is bringing home the money.

Igor felt he had lost his worth, and he was chasing a new/old religion to get it back.

We were bouncing along on the main highway to Novgorod. It was a remarkably broken, tattered stretch of pavement. I looked out the window at a tremendous flat expanse of land. Snow was melting, exposing splotches of black soil here and there in the fields. But perhaps field, singular, would be the more appropriate term, because there were no fences anywhere. A hundred years ago, little farmsteads must have dotted this countryside, but today it looked like just one giant field. Russian agriculture: industrial, immense, impersonal.

“Would you leave Russia, if you had a choice?” I asked Igor.

“I love Russia. She is the motherland. I love her. I would never leave her. I would like to see other parts of the world, to see your country, for instance, but I would always come back to Russia.”

Here and there, little houses, mostly drab, lined the highway.

“What do the people in these houses do?” I asked Igor.

“They are mostly widows. They have nothing to do. They get tiny pensions. They get two channels. One shows soap operas from Western Europe. Mostly they watch soap operas.”

“Could Lesley and I buy one of these houses and live there, maybe have a pig?”

“Sure, they would sell you a house. Maybe $500. $2,000 for a nice one.”

“Would the widows be nice to us?”

“Sure, they would come over, bring you some borscht.”

“Would they think it was weird if we didn’t watch television?”

“Very weird. They would not understand that.”

“Lesley, Lesley, how much age difference is there between you and John?” Igor chirped. (He usually addressed Lesley as Lesley, Lesley.)

Lesley did some quick math. “Thirty years.”

“Your relationship is perfect,” he said. “Lesley, Lesley, you are so young. You certainly do everything John tells you to do. It’s the way it should be.”

Lesley and I looked at each other and giggled.

I said, “I don’t know what she should do. I don’t even know what I should do.”

Lesley said, “Sometimes I do what he tells me to; sometimes he does what I tell him to do. We don’t have a rule about it.”

Love in Novgorod

Upon arriving in Novgorod, we took Igor out for dinner, in a restaurant built into the thick fortress wall that surrounds the Kremlin. (Many cities in Russia besides Moscow have a Kremlin, an enclosure of fortified walls protecting the inside of the city.) We ate in a vaulted room, its stone walls seven feet thick. The room had been built 1,000 years ago, about the time that Igor’s new religion was getting phased out by the Christians. As I watched Igor eat his fish soup, I wondered if there were spirits in this ancient chamber to which he had been praying.

Lesley and I settled into life in Novgorod. Lesley spent part of her days studying Russian, part doing volunteer work on various recycling programs. I worked on my writing and managed voluminous amounts of emails regarding the upcoming farming season at Angelic Organics back in Illinois. It was a romantic stretch of life for both of us, as we had time to explore each other, spend time with Lesley’s fascinating array of Russian friends (there were only about ten Americans in all of Novgorod), watch the figures in black walk through the snow from our window, and be out in Novgorod a bit.

Kostya, one of Lesley’s musician friends, a boyish, restless twenty-one-year-old, was writing his dissertation on the Yippie movement in the United States. We invited him and his friends over to Lesley’s apartment for a night of wine, vodka and to talk about hippies and yippies. (I had been a bit of a hippie myself.)

Kostya and his friends Diana and Andre came for the evening. Diana was pretty and buoyant, an actress in local theater. Andre was handsome, and elegant in a quiet way. Diana and Andre were lovers. Andre and Kostya played music together in a band that was dedicated to Shambala (a heavenly place).

Kostya said that he was having trouble writing his dissertation, as there were only official Russian accounts of the Yippie movement in the U.S. The official accounts said that the yippie movement was all caused by hooliganism. (Hooliganism is a word that has been adopted into the Russian language.) We spent the evening merrily talking about hippies, yippies, free love, and the Vietnam War. Although they were nicely dressed, clean-cut youths, Andre said, “We are all hippies at heart, me and my friends. We love nature. We aren’t run by money. We do what we believe in.” Much of this exchange was in English.

Diana, who seemed so excited to be with us, but who seemed rather out of the loop because she knew very little English, finally ran into the living room, came back swirling a pink boa, a red feather sticking out of her hair. She gleefully swished around for a while, and then announced with fanfare, “my grandmother lives in a barn, in a house that is a barn. I love my grandmother.”

Diana leaned towards the map above Lesley’s table and dramatically pointed to a spot in the northern hinterlands of Russia.

“She lives here!” Diana exclaimed.

“The people in my grandma’s village work hard all day, drink vodka at night, and every so often they go to the disco six kilometers down the road.”

Diana was gushing with love for her grandmother. She looked at me directly. “You come back to Russia. We go to visit my grandmother.”

The conversation turned to passion, what we each were passionate about, how to follow one’s passions in Russia, where choices are limited.

“I am passionate about music,” proclaimed Kostya. “I can always play music.”

“I am passionate about Diana,” exclaimed Andre.

Diana smiled and blushed. She said, “I am passionate about theater, but to make money, I work in emergency service, taking phone calls about emergencies.”

As they were about to leave, Diana sprang for the map, spread her arms out in a great sweep over Russia. “I love Russia,” she rejoiced. “I love Russia. Every bit of it!”

Bradn, the Lutheran apprentice minister I mentioned a while earlier, his friend Angela, Lesley and I went to a restaurant. Angela was visiting Bradn from Germany for a couple weeks. She was also studying to be a Lutheran minister.

We talked a bit about Finland, which was a few hours north west.

Bradn said, “I was in Finland once. It was the weirdest thing. Suddenly, everything was really neat and clean. I was in Helsinki. There was a great sense of order. For instance, all the manhole covers were in place. In Russia, so often they are off, and they stay that way. It would be so easy for kids to fall down a manhole.”

I asked, “So what do you think happens if a Russian goes to Finland and sees how different it is there?”

Bradn replied, “I think the Russian would think, oh, this is what happens in Finland, and something else happens in Russia.”

There was a party going on that night in the restaurant. It was a holiday, Men’s Day. (Women have their day, too, in Russia.) Three Russian women were putting on the party. One of the three was a friend of Bradn. She had told Bradn that Russians get most of their fun from vodka, and there should be a more natural way, and she was going to promote this natural way with parties.

Depending on what toy-military-medal one picked out of a hat at this party, one got a special treat, a kiss or a flower. The women were dressed in funny costumes, sort of a cross between Russian folk costumes and Disney garb—satiny, puffy, below-the-knee dresses emblazoned with big fruits and giant bumblebees. They sang the old Russian songs. They stamped, warbled, and fluttered. They twirled brilliantly inside their bumblebee and fruit dresses. The three women turned the normally grave Russians into fun, lively, singing, dancing spirits.

As I watched the darkly dressed party attendees cheerily bounce their way under the limbo pole, I wondered how the war was still playing out in their lives, how the thorough destruction of their town might still be lingering, festering, in conscious or unconscious ways. Sometimes people and cultures really do get on with life, after a big blow. Sometimes they just pretend to.

The Germans had looted or destroyed the 6000 religious icons that graced the ancient churches of Novgorod. They had ravaged and plundered thousands of early Russian manuscripts and printed books. They absconded with or destroyed a huge collection of paintings by the best Russian artists from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. (A few of these items have been trickling back to Novgorod since the war.)

The Germans were dismantling a tremendous monument The Millennium of Russia for transport to Germany to melt down into weapons, when the Russians finally routed them and reclaimed the rubble that was Novgorod. This monument immortalized the outstanding statesmen of Russia, along with all those who greatly contributed to the development of the country–its culture, science, art, literacy, literature and Christianity. German troops were going to the great effort, while waging war, of relocating to Germany this monument to a thousand years of Russian spirit, of Russian history. Almost nothing was left of the original Novgorod when the Russians marched in, save the shells of a few churches, and hunks of this sculpture, awaiting transport to the land of the enemy.

This night, the Russians at the restaurant were celebrating military valor in their town that had been completely destroyed by the Germans. After all, it was still their Russian town. So what if it had been rebuilt from scratch? They were partying in the motherland.

As the four of us left the restaurant, Bradn started talking about one of his parishioners. I don’t know what brought it up, maybe it was a conversation we had been having about lips, and kissing.

“One of the guys in my congregation was telling me recently about the rats in the work camp to which he had been sentenced,” Bradn stated. “The rats were really bad, but they didn’t eat the living. However, when someone died, they ate his ears off, and his nose, and his lips. They left everything else. That was the first way you knew someone was dead, by what the rats did. One night, my parishioner woke up and he was looking over to one side, and the guy lying beside him had no lips, and he quickly looked away, in the other direction, and there, on his other side, was another guy with no lips.”

“Bradn,” I said, “what does this do today? For how Russians are with one another, how they are about life?”

He replied, “they tell these stories very matter-of-factly. Who knows what scars are there? Who knows?”

“Russia is mysterious,” Bradn added. “One can’t understand it with the mind.”

Due to her being a student in the Ecology Department, Lesley had an affiliation with the agricultural branch of the University of Novgorod. Her professors knew a bit about me, and wondered if I would present on organic agriculture to the agricultural students. Russian agriculture, the dean revealed, is all about chemicals and huge scale, but the farms were broke. They had no money for inputs.

The Russian professors had considerable exposure to the conventional system of U.S. agriculture, which could not transfer to Russia, due to all the capital and technology involved. Occasionally, U.S. universities of agriculture hosted the Novgorod agricultural faculty, but back then (early 2000’s) the word organic was never mentioned. The dean hoped I could offer another way of raising crops, a more natural way that did not require much capital or new technology.

In the meantime, my visa was expiring and we only had a week to get an extension, so that I could stay in Russia to do my presentation.

To renew my visa, we explained, certified, got stamped, bribed, walked, got stamped, got questioned, called, went back, went ahead, called again, got stamped, got called, paid a bank fee, got asked why my visa was blue–it should be yellow.

The police who approve it need a gift, vodka.

Okay.

Oh, the police didn’t like the color of the visa.

Spasibo.

Try this hotel. They give extensions.

Thanks.

Oh, John is going to present on organic agriculture at the university? Have the university write up an official invitation. Make sure to get it stamped. Then it will be easy to get an extension.

Got it.

Why did you get this official invitation from the university? That will look very suspicious. Don’t show this invitation to the police, or you will never get your extension. You need an invitation renewal from your sponsor in Moscow.

Spasibo.

Why did you get the invitation renewal from Moscow? You don’t need that.

It’s the law, and you said to do it. The visa law requires it for an extension.

No one follows that law.

Why is John registered in St. Petersburg? The police will send him to St. Petersburg for an extension. They won’t do it here.

That’s a long trip.

At the very, very last minute (Here are your two bottles of vodka), the visa extension came through.

My farm Angelic Organics had been written up in a Russian magazine that was a sister publication to Organic Gardening. It was a nice five-page color spread in Russian, and Lesley and I decided to make copies to hand out to those who attended my presentation.

We went to the copy center, and the employees acted like why were we bothering them with a request for copies. How could we do that to them? There were many people working in this copy store, and not one of them seemed busy.

“Can we get these copies by eleven tomorrow morning?”

“Oh, that could be done.”

“Great.”

“But we are not going to do it. Probably not. Maybe, but maybe not.”

“If we leave them now, will it be more likely that they will be done by eleven tomorrow?”

“If you leave them now, they definitely will not be done by tomorrow, not by eleven, no way.”

“What if we bring them in first thing in the morning, will that make it more likely or less likely that they will be done by eleven?”

“More likely. But it does not seem all that likely.”

“How long does it take to do the copies? Your machines look very automatic. They look fast.”

“It doesn’t take long to make the copies.”

“Why can’t I get them by eleven, then, if I get them here first thing in the morning?”

“I don’t know. You might be able to.”

“Are you thinking that maybe there will be some other people here first thing in the morning, who will want copies done right away? If I get here right at opening time, will that make my chances better of getting them done right away?”

“It could.”

“Can you collate them with the machine?”

“Sure.”

“And staple them?”

“Yes, but you don’t want us to do that.”

“Why?”

“That will be expensive.”

“But it needs to be done. John has a presentation to give. We are in a hurry. We want it done.”

“No, you don’t. Not with a machine. Too expensive.”

“Can you do it by hand, then?”

“Sure.”

“Great, do it by hand. Does it cost when you do it by hand?”

“Yup.”

“How much?”

“Can’t say.”

“Will it cost more than it would cost to do it automatically?”

“Might. Don’t know.”

We spent maybe twenty or thirty minutes in this copy store, negotiating so many different aspects of making 150 copies, while the whole staff watched and listened. This was a store dedicated to copying, to business support. Many high-tech machines sat idle in this office, while we spent everyone’s time discussing our eight-dollar transaction.

I gave the presentation on organic farming to the agricultural class. It was in a huge university building that served maybe 2,000 students, and had one phone line to it. It was not an old building, but it looked like some of its gray walls were already falling off their frames. The street that led to the building was rubble.

Lesley had informed me about the Russian education system. “There is no money for textbooks. Students go into the classroom. The teacher reads from the textbook or from notes, and the students write down what he reads. Then they get an examination, based on what the professor read to them. There is little opportunity to ask questions in the class, to interact with the professor. It is simply not done.”

This synopsis of Russian education inspired me to begin my presentation with questions about who the students were, where they were from, what they hoped to do after graduating. I wanted to know my audience, and I wanted to create a space in which students could reveal themselves. My questions didn’t seem to register with the students, as I was asking them what they were about in life, and I guess they had never been asked to consider that, or were too preoccupied with survival to consider it.

I spoke on organic fertility and weed control as practiced on my farm. It was quite interesting to present to this mainstream agricultural group; there were several professors and administrators there, in addition to the students. They seemed quite open to hearing about organic methods. I reflected that a group of U.S. agriculture students and faculty would have been much less receptive to my presentation.

Afterwards, I asked the dean what these students would be doing after graduation. He said, “Selling things in big cities, retail jobs for most of them. A couple, if they are lucky, will get to go on and do agricultural research.”

“How many of them will end up on farms?” I asked.

“None,” he said. “The farms are broke. And they are all dismantled. There is nothing left of the huge collective farms. One person maybe got a mower. One person got a plow. Maybe someone got a harrow. Now they are trying to figure out how to get anything done. The curriculum at the university is designed to prepare students for these jobs that don’t exist anymore, that haven’t existed for ten years. That is the way the university works. It takes forever to get anything changed. So, we just keep training students for jobs that aren’t there.”

The dean added, “I am going to adopt your fertility system of leaving half the ground fallow in cover crops. We make so little money at the university. All of us who work here have to raise some of our own food, just to survive. I think your system might help me.”

On my last night in Novgorod, Lesley and I went to a nightclub to say goodbye to her friends, Bradn, Kostya, Diana, Andre and others. They mobbed us, hugged us, kissed me goodbye, hugged some more. I loved each of them.

As we walked into the snowy night, I said, “Lesley, there were so many people in that club who just kept looking at you. They don’t get to meet many Americans, and you are one, and they want to know you. And you speak their language so well. It is so perfect. You are a star in this city.”

“It’s you they want to know, John.”

We left Novgorod the Great in the morning.

Novgorod the Great?

After hundreds of years of waiting, of hoping, perhaps of intermittently petitioning the authorities in Moscow, Novgorod citizens could now call their city by its glorious old name again, Novgorod the Great. After being stripped by Moscow half a millennium ago of its status as the political center of Russia, after being overshadowed culturally for the last 200 years by St. Petersburg, after being smashed into bits by the German army, now, as ancient Novgorod incongruously hunched in its cloak of gray subsistence architecture and pride of place, by decree, it was officially, once again, Novgorod the Great.

To Moscow

With just a couple of days remaining before my extended vodka visa expired, Lesley and I traveled to Moscow, from where I would fly home.

The trip to Moscow was through mostly flat terrain. Snow fell much of the way, smearing the broken pavement, and bedazzling the tall pine trees that occasionally lined the road. Numerous cars and trucks had spun out into the ditches. We passed through many villages, with their mysterious mix of drab and festively painted cottages.

Along the highway, the villages sold things to the travelers, sometimes under awnings, but more often, just out in the elements. Everything, including the sellers, was covered in snow.

Each village had its specialty. One had stands of fish and pickles. Another sold blankets. In the middle of the open country was a car with bed pillows stacked high over its roof and its hood. In a later village, small patches of snow clung to dozens of prominently displayed beach towels featuring tropical birds, Cadillacs, and naked women. I wondered how it would feel after a shower to rub myself dry with one of these garish towels.

Moscow is the Manhattan of Russia, a flamboyant splay of monuments, traffic, parks, gleaming (and shabby) high rises, and honed entrepreneurialism. It pulses, throbs with life. How had Moscow come about, with its flair, its vitality, and its extravagance, in a country so somber?

Upon returning from his tour of the United States, Khrushchev allegedly had decided that the reason the U.S. was so rich was all the corn planted there. He made a decree that no potatoes or carrots could henceforth be grown on the collective farms, only corn. For the next five years, Russian agriculture was all about corn, and the citizens went without potatoes and carrots. Or so one Russian told me.

Perhaps there was some truth to this Khrushchev story. The rest of Russia, at least what I had seen, seemed so plundered. The countryside was so stripped of life. Perhaps it was the once fertile fields, the once robust farms of the country that had somehow fructified Moscow. Whatever the emptiness was in the countryside, it seemed there was a corresponding fullness, robustness in Moscow. I imagine there were many policies for mandatory tithing–quotas on mines, forests, fisheries, and oil fields– that were designed to transfer wealth from the outer reaches of the Empire to this robust mecca of cosmopolitanism.

The following is an account by Lesley of our first night back in Moscow.

The Orange Coat

by Lesley Freeman

“Due to heavy snow during the day’s drive from Novgorod to Moscow, John and I were an hour and a half late to meet our friend Nastya in the Metro station. I imagined Nastya waiting for us on a bench against the station’s white marble wall, the noise of the screeching trains in her ears. She’s asking the various people who take seats next to her for the time before they jump up to greet their dates, friends, and other individuals and hurry off with them. I thought she might be gazing up at the Metro station’s ceilings: high, arched, and lined with outdated mosaic images of Soviet life–an artistic journey available only to those Metro-goers who are too early, too late, or waiting.

“Our driver dropped us off across the street from where we needed to be, so we rushed down into the nearest underpass, the Moscow version of a crosswalk. Little shops lined the grim interior of the tunnel. As we rushed through, I stopped short in front of one of the shops and excitedly pointed at a bright orange coat. John liked the coat, and I liked the coat, but we were late so we rushed on.

“Maybe Nastya would still be there, we mused as we rode the extensive escalator deep into the area underneath Moscow’s famous Arbatskaya region. She wouldn’t wait an hour and half, would she? No, by now she’d be late for the hippie dance class she had invited us to. But maybe she was there. We glided off the escalator into a long, bright marble tunnel choked with masses of people and lit by monstrous metal chandeliers covered with images of hammers and sickles.

“We walked forward, paying as much attention to the masses of moving people as to the possible presence of Nastya. But Nastya was gone. John and I stood there, getting knocked into by rushing Muscovites. We slowly went back to the escalator.

“We stood at the top, a bit out of the way, watched people go by, feeling sad that we’d missed our friend. Both John and I stood a bit more, looked at each other, looked at more of the Soviet chandeliers.

“John suggested we go back to the little shop in the underpass and look at the orange coat that had caught my eye. He was getting excited at the prospect of me having the new orange coat he knew I wanted, and the excitement infected me. We went back to the shop. The coat hung on the door where it had been before. We walked in. Women’s clothing lined the walls. I took off my shabby corduroy jacket and John slipped the orange work of art onto me. I displayed the coat for John; he ooohed. I spun around in front of the mirror, and the saleswoman ahhhed. I was dancing in the coat.

“I wanted more room in that tiny little shop so John and I could spin around and embrace and be in love and I‘d be in the amazing orange coat.

“The saleswoman saw my danc-ey movements, turned on the radio, and started dancing with me. She wore an old whitish loosely knit sweater with light blue and pink highlights with tightish black stretch pants. Her greyish blond hair matched the sweater and her middle-aged face was creased by what had probably been a difficult Russian life.

“John began dancing, and we were all giddy and laughing, the saleswoman especially. She was so thrilled to meet us, she insisted, from way deep inside her soul.

“The three of us danced in a little circle, danced in a group hug. John and I were giving in to the flow of this experience, and we both loved the joyful connection we were making with this random woman. And my my my, did she love the connection she was making with us. She bounced right out of any hardship from which she may have been suffering.

“There was more group hug-dancing and the woman kissed my cheek. The music was loud. The shop was tiny. She asked us if we were married. John and I laughed, looked at one another lovingly. No, we smiled, we’re lovers.

“She told us John was her dream man, that he had the right sportsman-type shape, the right face, the right way about him. She waved her arms around close to his torso to demonstrate that she more than approved its form. She stepped back and admired him, her hands cupping her cheeks which had become extremely blushed. She’d never met anyone like him, she maintained. Did John know anyone like himself in America? She was looking for a good man with the right body who would be her perfect husband.

“John was being his considerate self. He’s a natural matchmaker. He looked at her with understanding, and seemed willing to help her with her search for a man.

“I was ready to pay for the coat; I had the rubles out.

“She grabbed John and danced with him.

“I danced to myself in the mirror. The orange coat was amazing. It matched John’s furry green and orange neck scarf. I turned to look at his dance with the woman, perhaps for some guidance; John always seems so composed and self-assured in bizarre situations. “I caught John’s eyes and smile which communicated something like “can you believe what’s happening!?” I smiled back at John. The woman had him in her grasp.

“When she finished appraising and almost fondling him, she remembered me and insisted in an apologetic voice that I shouldn’t be jealous, he’s just so perfect. I know it, I thought, still entertained by the situation.

“I finally filled with shock, as it became clear what a fantasy world this woman lived in, completely unable to control herself, unable to resist her desire.

“I looked at John, a person who hates saying no to people, a person who would rather give people money, time, and affection than see them lacking or upset or rejected. John helped this woman to feel loved and accepted.

“I gave her the money I had been holding. She took it but never counted it. Red-faced, scared, and sincere, she insisted I not be jealous, that my man was simply the very perfect man. I nodded and, somewhat stiffly, hugged her and smiled some reassurance, hoping to take the edge off her possible upcoming progression of emotions.

“And the saleswoman passes the hours by in her tiny store, looking out into the underpass through an unclothed section of window, perhaps hoping to see John again. Disappointment, shame, satisfaction…who knows what her emotions were, became? But, without a doubt, a piece of her fantasy came alive that day.”

End of The Orange Coat by Lesley Freeman

(Years later, Lesley told me that she had held on to the orange coat as long as possible, but every time the coat got wet from rain, it smelled more and more like burnt rubber. Finally, it smelled so much of burnt rubber, she had to discard it.)

The Sixth Epoch

Rudolf Steiner said that the sixth great epoch in human evolution would be centered in the Slavic world. (The fifth epoch is Middle European; the fourth was Greco/Roman; third, Babylonian-Assyrian-Chaldean-Egyptian; second, Persian; and the first was Ancient Indian. Each epoch lasts about 2,200 years.) In a lecture on May 30th, 1908, in Hamburg, Steiner said that the “impulse…for unity and brotherhood…will eventuate in the sixth epoch.”

It is tempting to think that Russia is slowly preparing for its eventual mission in the unfoldment of human culture, that much of its apparent dysfunctionalism and clumsiness is simply the process by which it is staggering gradually to the forefront of earned world leadership based on love between human beings. The epoch timeline would have Russia taking front stage about 1,600 years from now, so there is no big hurry. Ironically, the dominant characteristic of the sixth epoch will be free will.

The Russian preoccupation with subterranean beauty via their subway systems is perhaps a foreshadowing that the Slavic peoples are preparing for their eventual role of benevolent world leadership. They are starting where foundations will have the most endurance, deep within the earth.

The subways in Moscow are splendid in their beauty–bright, gilded, graced with opulent chandeliers. Reliefs of hammers and sickles are scattered throughout the subterranean chambers, ornamenting corners and railings. Immense mosaics of robust working men and women, toiling to farm and to run the factories of Russia, preside on the ceilings and gleaming marble walls. Great moments of Russian history are lavishly commemorated in sculpture and painting in the hallways and chambers of the palatial underground passages. Statues of Lenin and other military leaders loom above the bustling Russian crowds.

Perhaps the woman who sold us the orange coat is playing an important role in the unfoldment of the glorious Slavic epoch to come.

Lesley and I went to the fancy bagel store, Great Canadian Bagel, that we had visited in the middle of the night several weeks earlier. Julia ran towards us, gave us big hugs.

“I got the paperwork done again,” she smiled. “He will be released either in May or in the fall. I am so excited to be getting my husband back.”

“Wonderful, Julia!”

“Did you two get married?” she asked.

“No,” I replied. “We didn’t get married.”

“Please invite me when you do. I really want to come to your wedding.”

Crash?

Upon leaving Moscow for the airport, Lesley and I were in an accident. I later pieced together that a driver in the opposite lane of this eight-lane highway had done a U-turn. The car crossed the median into our lane of ongoing traffic and clipped a car ahead of us, causing that car to do a 180-degree spin.

This car that had once been ahead of us pointing forwards was still ahead of us, but now with its front end pointed in our direction, going backwards down the highway. Imagine, it had been going forward at, say, sixty miles per hour, and suddenly, because of this 180-degree pivot due to being hit by another car, this car was no longer facing forward, but facing backward, now careening down the highway backward at fifty miles per hour; it was going in reverse at fifty miles per hour.

The driver stared at us through her windshield, a look of horror and helplessness on her face.

Accidents often seem as though they are occurring in slow motion. This collision that was about to occur with our car was so gradual, I felt that time had offered to almost stop, giving me time to ponder life, to ponder Russia, to ponder my soon-to-be mangled body. This woman seemed to be barreling down on us as we skidded towards her on the busy eight-lane highway. It seemed like it took forever for us to get within striking distance. Finally, the two cars met. I awaited the crumpling hoods, the shattered windshield, our driver lurching into the steering wheel, crumpling his chest, as Lesley and I would be hurled over the front seat through the windshield, ending up on the hood of the woman’s car.

“I felt that time had offered to almost stop, giving me time to ponder life, to ponder Russia, to ponder my soon-to-be mangled body.”

None of this happened.